Lavatia Khojas

The Lavatia of Oman: Arabs or Khojas – An Intriguing Paradigm of Binary Identity

Hasnain Walji

As we came to land at Muscat airport, our guide, a Muscati scholar originally from Iraq and now working in Holland, had joined us for the Khoja Studies Conference in Mumbai, pointed to Matrah, situated a few miles west of Muscat. Set amid volcanic hills, Matrah was the hub of business and is the location of Sur al-Lavatia – an area as mysterious as the people who used to live there and still own the houses there. Located at the heart of one of Oman’s major tourist spots, Matrah is flanked by a corniche walkway where cruise ships offload hundreds of tourists.

Nestled just behind the bustling souq, one of the oldest in the area, and the waterfront is Sur al-Lavatia (sur in Arabic means a fortified enclosure). For many years, this picturesque district was closed to all except members of the Lavatia community.

Salma Damluji, in her book The Architecture of Oman writes ‘The Portuguese are thought to have originally founded the settlement, since a Portuguese garrison is recorded there in the 17th century. It is possible that after the Portuguese were expelled the area was given over by the Sultan to the Muscati Khojas then known as Hyderabadis.’

Today, though not officially closed, this walled quarter is discreetly guarded and continues to intrigue tourists looking to get a glimpse behind the gates and walls

Fortunately for us, our host, a local Lavatia businessman, al-Haj Jawad Fajwani, gave us a rare guided tour of the mansions behind those walls. Although most residents have now moved to posher neighborhoods of Muscat, the houses are still owned by the original families, who converge there for Muharram commemorations as well as other epochal dates in the Shia Calendar.

Interestingly, the outward array of buildings along the beach front and some houses inside the encampment have arched windows and balconies displaying the intricate lattice work that looks like traditional Gujrati residential architecture similar to those in Zanzibar and Mombasa. This is in stark contrast to other Muscati buildings which have more austere Arab style exteriors and no balconies. The homes Sur-al Lavatia are built close to each other - are a vivid reminder of the closely-knit community of wealthy merchants who lived there for over 150 years.

Why the Interest in Lavatia

This was why the Khoja Heritage team comprising of Shaykh Kumail Rajani and I had come to explore the origins of the Lavatia people.

And the question we wanted answered was do they have a Khoja linage or are they of Arab decent?

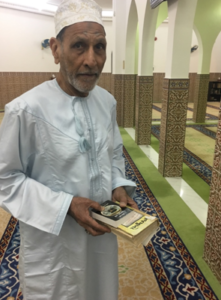

At the first encounter the answer almost stared us in the face. On entering the Al-Rasul Al-‘zam mosque for Maghrib prayers, we were greeted by an elderly gentleman carrying the Gujarati Majmuo by Haji Naji. We exchanged brief pleasantries - we speaking Kutchi and him responding in a language akin to Kutchi, for which the Lavatia term is Khojki.

Historians have been puzzled by this enigmatic juxtaposition of the Lavatia either as Sindhi Khoja or as people of Omani Arab descent who had lived in Sindh for a couple of centuries.

British Imposed Identify – yet again!

Yet again, we need to ‘thank’ the British Imperialists for this imposed identity. A simplistic document called The Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia was created by the British Government of India to provide colonial administrators with a ‘cliff notes’ type of ready reference material which placed colonized subjects into neat little pigeon holes for ease of governance. According to this Gazeteer, in a section dealing with the Gulf region the al-Lavatia are listed under K for “Khoja sect”. Notably the entry suggests that in Oman, the Khojas are known to the Arabs as “Lavatia” and that they are also commonly referred to as “Hydrabadis”. This British narrative, which has then been adopted by some Orientalists, claims the Lavatia have their origins in the Sind area and are of Sindhi decent. Indeed, while the Lavatia are called Al-Muscati in Kuwait and Bahrain, those living in Oman have surnames such Nadwani, Najwani Sajwani, Kashwani, Fajwani etc, suggesting the Sindhi provenance.

The orientalist, Laurence Louer, states in his book ‘Transnational Shia Politics: Religious and Political Networks in the Gulf, that the Lawatis were ‘Khoja Ismailis who migrated to Oman from Hyderabad in the 19th century, before converting to Twelver Shi'ism following a dispute with the leadership of the community’.

Referring to the impact of the trials and tribulations of the 19th Century Khojas of the subcontinent Amal Sachedina in her thesis ‘Of Living Traces and Revived Legacies: - Unfolding Futures in the Sultanate of Oman’ suggests:

Memories of their regional ties with other Khojas based in India are recalled through the flotsam and jetsam of washed up fragments that have been passed down through the generations. These are premised on division and conflict rather than commonalities. A number of the al-Lawati recalled that the main mosque of the sur once housed the jamā’at khāna …… One member of the community recalled how a woman of the sur took up all of the vessels and materials related to the jamā’at that was once within the great mosque, went onto the beach area and threw them into the sea. Those families who supported the Aga Khan, twenty in number, were asked to leave the sur and the remaining families, the majority, formally became Ithna’Asharis. The building that was once the jamā’at itself became a wholly Ithna’Ashari mosque.1

1 1 Sachedina, Amal. (2013). Of Living Traces and Revived Legacies: Unfolding Futures in the Sultanate of Oman. UC Berkeley. ProQuest ID: Sachedina_berkeley_0028E_13852. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m5935g2s. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5ts8978s

Folklore and Legends Galore

While the nuances of the ethnography of Khoja/Lavati nexus seems to be nebulous, the various folklores and legends of their origin including the very name ‘Al-Lavati” have been pragmatically framed to buttress their establishment in Omani Society- an intriguing case of a binary identity formation.

As for the name, the colonial-era ‘Gazetteer’ suggests that the term Lavatia may be derived from the term “Indin lota”, (water jug), which they used to carry when they first arrived in Oman. While the term was originally used in a pejorative sense, today it is accepted as a formal term identifying the community’s lineage. Interestingly, while the term Lavatia is used when community members introduce themselves to outsiders, I observed that they still tend to use “we Khojas’ in their internal conversations!

The Lawati scholar, Jawad al-Khaburi al-Lavati (1913-1984), who was in exile in Mumbai and Karachi, presents a counter narrative however. In his book ‘al-adwār al-‘Umaniyya fi’al-Qārra al- Hindiyya: dawr Bani Sāma b. Lu’ay ‘ he contends that the al-Lawati are descendants of an Arab tribe, Banu Sama’ bin Lu’ay who had fled to Sindh around 279/892 - this firmly places the Muscati Khojas within the Arab tribal milieu.

In local folklore we find yet another discussion by Muhammad Taqi Hasan Omani who suggested that the Lawatiya were descended from Hakam bin Awanat al-Lat, who commanded the first Arab invasion of the Indian sub-continent.

Given these contestations, it is no wonder when we met the current Head of the 10,000 strong Lavati Community, Hajj Abdulhusein Bhaker Jaffer, he sternly suggested that the present and the future were more important than history. In quickly changed the subject by describing the design of the grand Mosque the Lavati Community was building to serve the future generations, he was perhaps hinting that faith is a great equalizer and that the discussion about cultural identity is less important,.

Promoting ‘Arabness’ and Downplaying ‘Khojaness’

Underlying such a cautiously pragmatic position, we perceived creative tensions that seem to simmer underneath Omani society. While the Lavati community tries to assimilate in Omani Arab society and promotes its ‘Arabness’ and downplays its ‘Khojaness’, the wider Omani society still seems to perceive them as outsiders. Despite their wealth and influence, one feels an unspoken level of insecurity even amongst the most established. This is an interesting commentary on how minority identities are set and recognized within a society - by no means is this a unique situation to Oman but has been encountered by the Khoja communities in many other parts of the world.

This notion of the Arabization of the Muscati Khojas is a relatively recent phenomenon. Up until the 1970s, their passports and other legal documents used the term ‘Hyderabadi’. There was then a was a move by Community elders to reframe this identity to one based on al-Khabori’s narrative that Lawati are decedents of Usama bin Lu’ay. This view has now gained significant currency in identity formation of the Lavatis to have resulted in being an officially recognized tribe descended from Bani Sama’ bin Lu’ay, one of the earliest tribal groups of the Oman region to go to Sindh.

Regardless of historical accuracies, given the current geopolitical movements in the Middle East, this evolved identity seems prudent and pragmatic enabling the Community to project a strong base as they ascend to higher positions in government, and more importantly get an even greater share of the newly burgeoning economy. In this they ironically display a typical Khoja trait of knowing exactly which side of their bread is buttered.

Today. the Lavatis play an increasingly important role in the development of the modern infrastructure of Oman. With their level of education, wealth and business acumen, they hold high positions in the ministries, oil industry as well as diplomatic circles.

What lessons the rest of the Khoja world could learn from this binary identity formation that generates such paradoxes amid much wealth and power is a question I leave to our perceptive readers and social scientists.

For me, despite all the ethnographic mumbo jumbo, meeting a number of very hospitable Muscati Khojas and observing them interact with us and each other made me feel very much at ease with them. I came away with a feeling that they must be my fellow Khojas. The image of the Majmuo in the hand of the elderly gentleman in the mosque dissolved any last iota of doubt. Indeed the only thing that could convince me otherwise would be a DNA test. Being hosted with such genuine hospitality and goodwill, I simply could not bring myself to make that request of our hosts, lest it shatter for them an illusion, such as the one built by reading Kipling about of the glory of India!